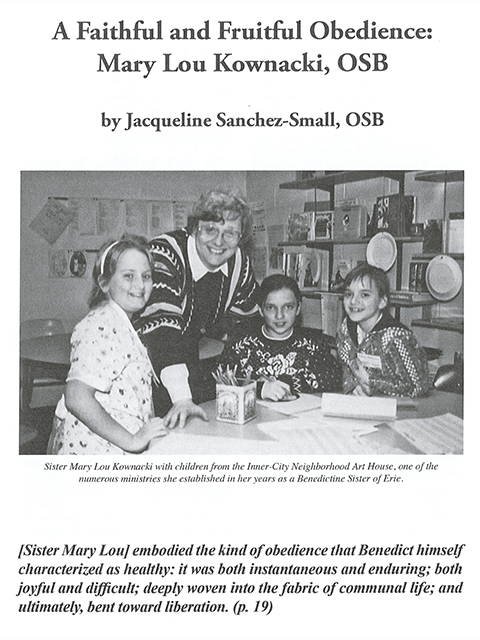

Sister Jacqueline Sanchez-Small's essay, "A Faithful and Fruitful Obedience: Mary Lou Kownacki, OSB" appears in the 2024 Spring/Summer issue of Benedictines magazine. Below are a few paragraphs from the piece that captures Sister Mary Lou's spirit. Contact Jennifer Halling, OSB, to subscribe to Benedictines: [email protected].

Obedience, then, is a high-stakes matter. An over-simplified understanding of what it means to be obedient can stunt psychological and moral development. A truly distorted understanding can create—and has created—immense suffering, on micro and macro levels. Understood and lived out well, though, obedience can be, and always has been, a crucial part of the path to sanctification.

Sister Mary Lou's lifelong journey toward holiness, and her complicated and nuanced relationship to authority, raise important questions and nuances for those who are seeking to live a mature and well-considered iteration of obedience. Firstly, her life asks us to consider who, or what, deserves obedience. Secondly, she embodied the kind of obedience that Benedict himself characterized as healthy: it was both instantaneous and enduring; both joyful and difficult; deeply woven into the fabric of communal life; and ultimately, bent toward liberation. ...

This framework of obedience is, of course, far less straightforward than the traditional notion of a top-down structure in which obedience can be demanded because of one's standing within a hierarchy. Still, it is characterized by the very same qualities that Benedict identified as essential to obedience in the fifth chapter of The Rule of Benedict. The monastic is urged to obey immediately the commands that come to them (RB 5:1-9), lovingly and without self-interest( v. 10-13), and joyfully (v. 14-16). These traits were on full display in Sister Mary Lou's obedience and in her basic approach to life.

She was not one to hesitate but had a great sense of urgency in matters of justice and a basic trust in her ability to judge what was right and what was wrong....

Love, rather than self-interest, lay at the root of her ministries and her political work, and she was willing to suffer for the sake of the causes she undertook. But she never took on a kind of martyr mentality or saw her faithfulness to the marginalized as a reason to become cynical or somber. And whether she was on the picket line or establishing a soup kitchen or laboring over the kinds of administrative minutia she really disliked, her sense of duty was never grudging. Instead, she had a seemingly inborn joie de vivre that infused her ministry, and her various efforts were more inspired by the vision of what beautiful things might be possible than they were by a rage or disgust at the ugly realities of the present.